The disaster of New Ireland

Can you imagine taking responsibility to pack up your whole family and move to an unknown land? It took desperation, hope and faith. Everything took a long time. There were no planes, but a slow ship that took three months to cross the ocean. There were no phones, let alone Internet, and no one to provide photographic evidence of what actually lay ahead in the promised colony of La Nouvelle, France. The expeditioners’ deep suspicion of the new Italian government meant they did not believe the officials’ warnings about their destination.

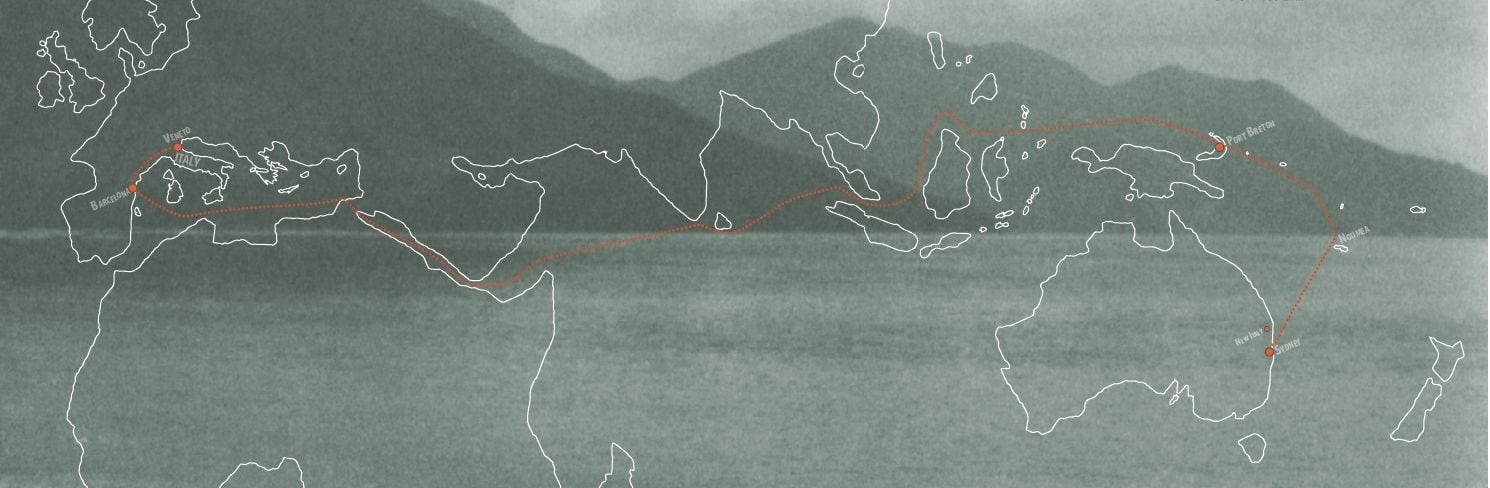

The colonists left from Barcelona on the 9th July 1880 on board the ‘SS India’, previously a sailing vessel, now converted to a steamer. They were bound for a barely inhabited island off the coast of New Guinea. The Sydney Morning Herald claimed there were 260 Italians and 30 French passengers (the exact number is unknown). Rotting food, overcrowding, illness, death and the increasing tropical heat made the trip very difficult. Ten of the Italians died on the voyage.

What horror must have been to arrive at Port Breton, the promised bustling settlement of the new colony on New Ireland, to find nothing but a couple of roughly built huts in a clearing of dense rainforest. Girolimo Tome later told the New South Wales Government: “…nothing was prepared for us; we found nothing but rocks, and stones”. Men, women and children quickly set about clearing, ploughing and planting crops. However, almost on the equator, the heat was overwhelming and torrential rains soon set in. Fever overwhelmed many. While plenty of equipment had arrived on board, including a crate of dog collars, there was very little food. What there was, Luiga Tome told the New South Wales commission, “was not fit for dogs”.

The Tomes lost their baby, and another twenty three Italians died on the island. Starving and desperate, they all abandoned New Ireland on 20th February 1881, bound for new Caledonia, Noumea, with the intention of reaching Australia. However, the ‘India’ was declared unseaworthy on their arrival, and the Italians became stranded in terrible conditions. Fifteen more died.

On 2nd April 1881, the Sydney Mail, which had been following the dreadful tale, said of the venture: “The end has come suddenly, and is clearly traceable to one or two things – either gross mismanagement, or heartless indifference on the part of the projectors. Whether any Australian government will care to meddle with so tangled a web seems doubtful: otherwise, they might find a home in these colonies, to the mutual advantage of themselves and of Australia.”

Historic Tome’ Rifle

Owned by Girolamo Giovanni Tomé of Orsago, Italy, this musket travelled with Girolamo, his wife Luvigia and their 5 surviving children on the Marquis de Ray’s expedition of 1880-1881. (Photo 1 of the family taken in 1890s.)

Girolamo and Luvigia’s experiences from the expedition are documented in the “Minutes of Evidence” from the NSW Government’s Inquiry by J. Milbourne Marsh and George F. Wise 1881. Both Girolamo and Luvigia spoke (via an interpretor) at the NSW Government’s Inquiry.

The family story is that the rifle was used by Girolamo Giovanni Tomé at the Battle of Solferino on 24 June 1859. Solferino is about 200km west of Orsago.

Photo 2 is believed to be Girolamo in his military uniform.

The Battle of Solferino was fought as part of the wider battle for unification of Italy. The horrific injuries and lack of any medical support to the thousands of injured soldiers was documented by a Swiss businessman, Henry Dunant, who was travelling through the area at the time of the battle. In 1862 he published his account, “a Memory of Solferino”. His proposal to create a society of neutral and impartial volunteers to care for the wounded in times of war was accepted and within months the Red Cross Society (which still exists today) was formed.

Source: http://www.redcross.org.uk/About-us/Who-we-are/Museum-and-archives/Historical-factsheets/The-Battle-of-Solferino – (no longer valid)

See: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Battle_of_Solferino

Girolamo Giovanni Tomé and Luvigia are buried in the Pioneer’s Museum at Liverpool.

Photo 1: The Tomé family est 1890s

Photo 2: Girolamo Giovanni Tomé in Military Uniform

Photo 3: Headstone of Girolamo Giovanni Tomé and Luvigia at Liverpool Pioneer’s Park (serpentine wall)

The rifle was passed to Nicholas John Catlan (prev. Catalano), great grandson of Girolamo. Nick passed away on 1 Dec 2017, aged 83. He was always a keen supporter of the New Italy Museum, so it is very fitting to donate Girolamo’s rifle to the Museum for their display by Belinda Patterson nee Catlan (Nick’s daughter. Executor) 18/12/2017

Bricks and a Bible – Surviving the Journey

A book for the soul.

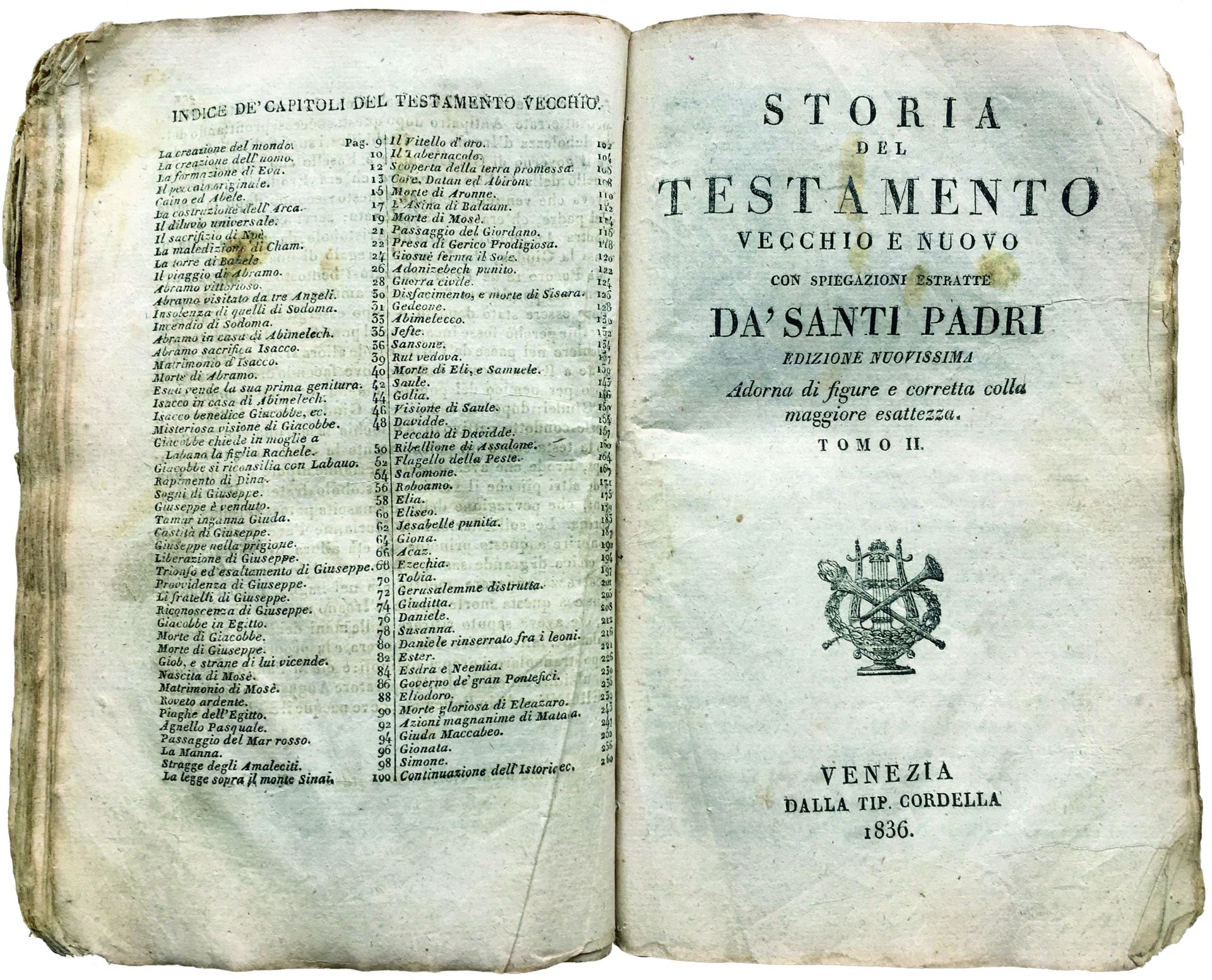

Antonio Bazzo was 36 in 1880, when he packed this book amongst his meagre possessions to travel with his family, and fellow contadini from Cologne, Veneto to La Nouvelle France. It contains the Bible stories from the old and new Testaments. Their faith sustained them through their ordeals and bound the community together.

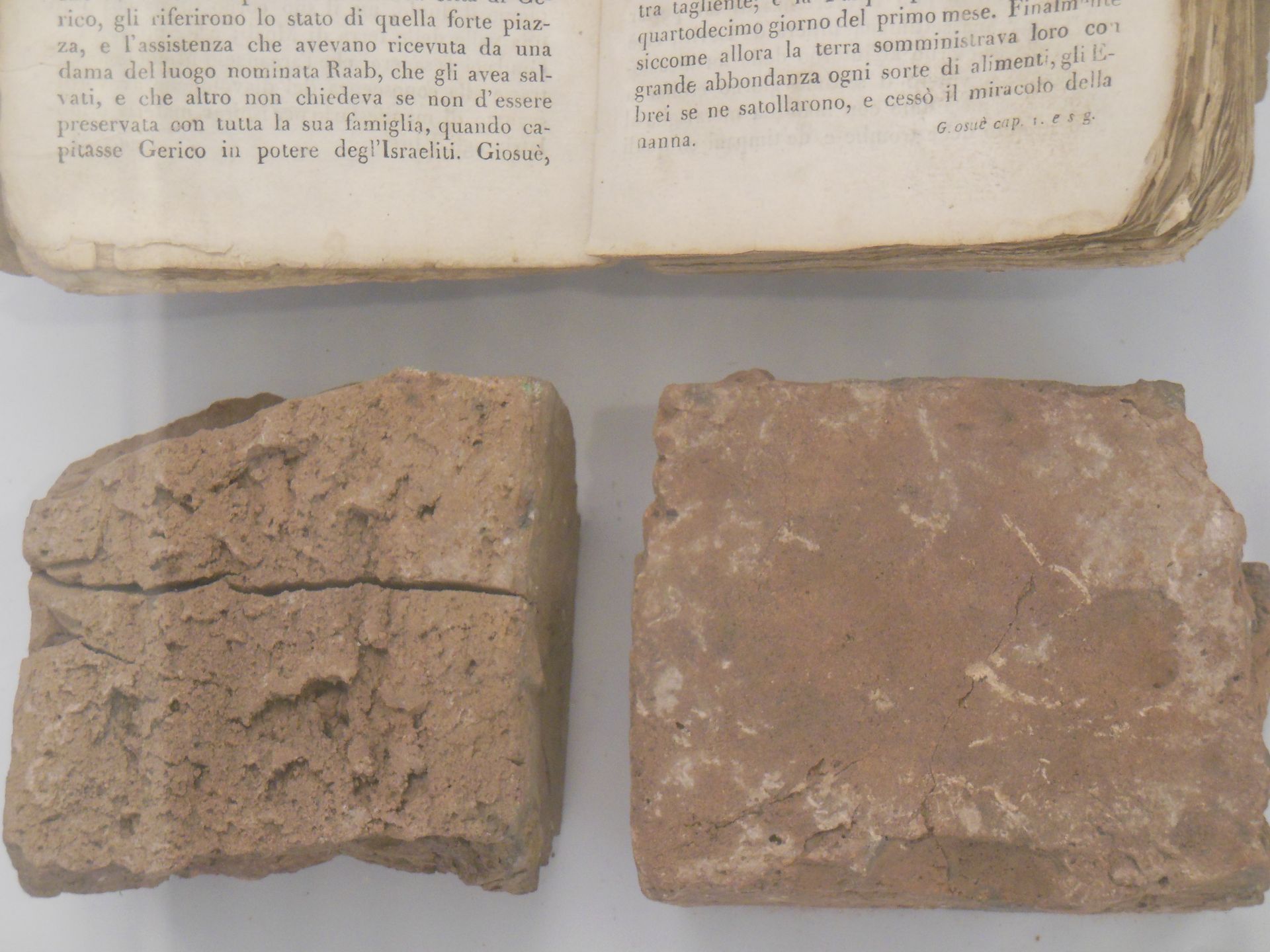

Bricks for a green church

Since it was planned to build a Catholic Church at La Nouvelle France, 180,000 bricks were loaded as ballast on the first of four expedition ships to leave Europe – the Chandernagore. They were intended to be used as foundations and the lower part of the structure. These bricks were probably loaded in Le Havre, and so would be of French manufacture. Upon arrival at Port Breton, all were unloaded onto the beach, and there they stayed when the site was abandoned. Some were later salvaged and used for buildings on nearby islands, but many remain there to this day.

<< (3) The Swindler: Marquis de Rays

>> (6) Shipwrecked Mariners